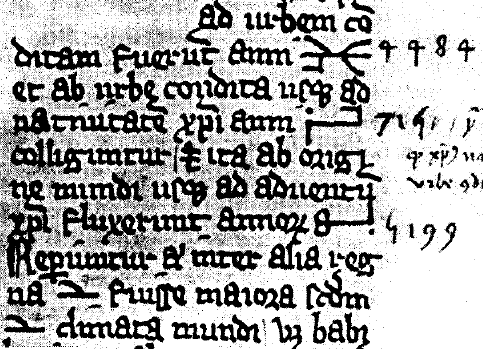

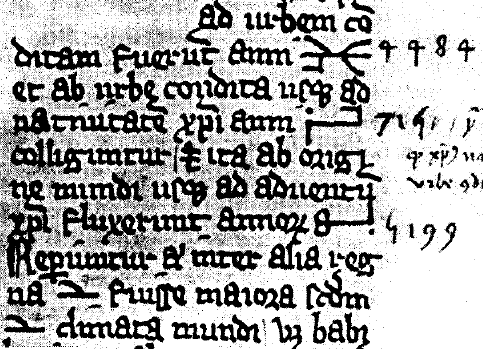

Probably this isn’t particularly relevant for the VM as such, but I found it interesting nonetheless when Wikipedia today pointed my attention to Cistercian numerals.

From what I gather from the article, these numbers or numerals were in limited use through the latter part of the European middle ages, and are particularly interesting since they for the first time (in Europe), and independently of arab-hindu numerals developed a “digit” system where the numeric value of a character would be indicated by its position within a number. (In other words, as opposed to roman numerals, where “M” would always indicate “1000”, in the arab-hindu system the character “2” will represent a different value depening on whether it’s been inserted at the end of a number (where its value is always “two”) or anywhere else (in the last-but-one position, the value will be “twenty”, etc)

The Cistercian system takes a little to wrap one’s head around it, but once you get the idea, it’s not that difficult: There is a basic “stave”, vertical or horizontal, plus nine different shapes, representing digits “1” through “9”. The digit shapes are attached to the four “corners” of the stave, with each position representing the ones, tens, hundreds and thousands, resp. (Top left could be the tens, top right the hundreds, etc — details vary according to the particular use) This means that one character consisting of a stave and four digit symbols attached to the corners was enough to represent any integer between “1” and “9999”, so it was fairly powerful, compared eg to roman numerals.

You will notice that there is no need for a zero in this sytem, and probably this was also the reason why it never saw widespread application: If zero was lacking, the artithmetic power of the system was limited (doing divisions would still have been a nightmare, for example), and the Cistercian numerals stayed limited to page foliation and simple numbering tasks, as opposed to calculations. So near, and yet so far to have invented a real rival to arab-hindu numerals…

So, what impact does this have on the VM? Little in particular, since none of the VM characters much resembles the Cistercian numerals, and it also doesn’t look like the characters or words of the VM were composed in a directly comparable manner. Yet, the Cistercian numerals show a surprisingly sophisticated encoding system for numbers, and so it’s not implausible that the VM author employed a similarily complex system for enciperhing his text.

The general view is that in the times of creation of the VM (15th century, as the mainstream opinion is) (quiet, Rich!), not much more than simple monoalphabetic substitution ciphers were in use, hence the VM must be considerably younger, or contain nonsense.

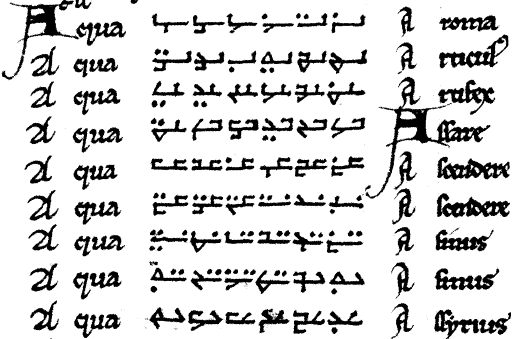

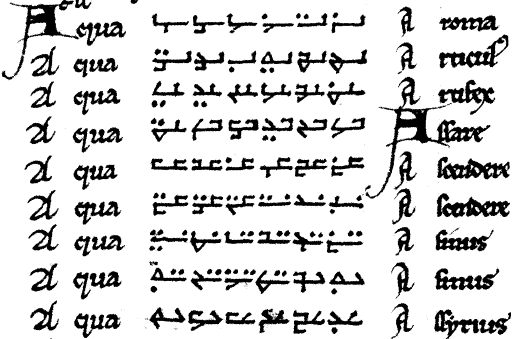

On the other hand, the above picture shows a concordance from a 13th century (sic) MS, twohundred years before the creation of the VM. The Cistercian numbers in the center column refer to occurences of the word “aqua” in the corresponding manuscript, giving the page or columns numbers where the word occured. Now it would only be a small leap for any would-be encipherer to create his ciphertext by replacing his plaintext words with the numbers corresponding to this word from his concordance — in this example, he would have plenty of Cistercian numbers to chose from to represent the word “aqua”. Provided the recipient of this message has the same MS available, they are able to reconstruct the plaintext by simply looking up the numbers written in the ciphertext.*) This system**) would have two advantages:

- The message is safe as long as anyone trying to intercept it doesn’t know which MS was used for reference.

- It’s a poly-subtitution cipher, meaning one and the same plaintext word can be enciphered in different ways, making any codebreaking attempt so much more difficult.

And, as the Cistercian numerals show, such a system would have been within the intellectual grasp of any educated person in central Europe during the second half of the middle ages. So maybe it really is time to scour the VM for clues to some more complex enciphering systems beyond simple subsitution.

*) Of course this isn’t practical in this example, because on one page of the reference MS there would be many words found. But rather than refering to the page numbers of the word’s occurences, one could use the position of the word in the stream of the text (numbering all the words in the MS as they occured).

**) I know it has a name, but I’ve forgotten what it’s called.

(Images taken from Wikipedia.)

Ha, und der Dummkopfen werden niemal looken through meine perfekten disguisen as eine harmlessfully Wonderer!

Ha, und der Dummkopfen werden niemal looken through meine perfekten disguisen as eine harmlessfully Wonderer!